September 3, 2025

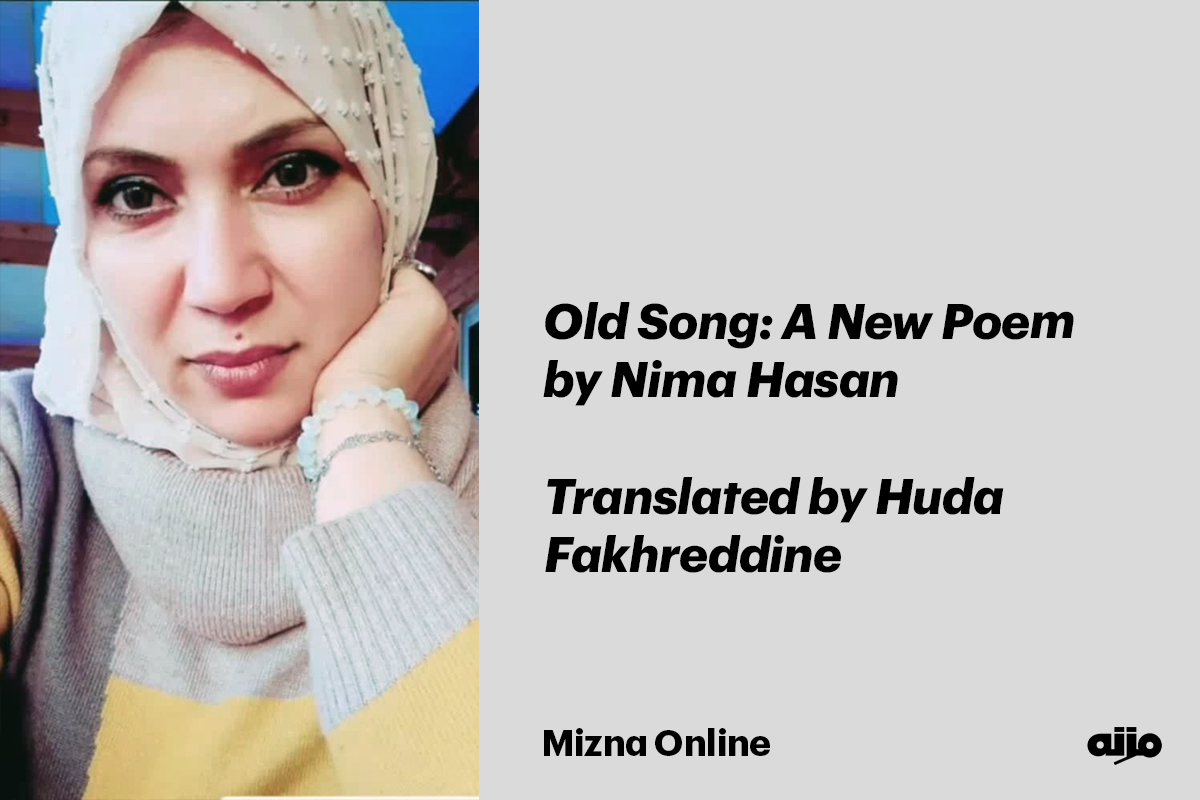

Old Song: a New Poem by Nima Hasan

trans. Huda Fakhreddine

In Beirut this July. I wake up, as we all do, to images of starving Palestinians—humiliated, hunted down, spectated, documented, and yet abandoned every minute to the monstrosity and performativity of a complicit world. In Beirut, a city holding its breath, anticipating something to descend upon it—nothing good—Gaza is always on my mind.

A message on my phone jolts me from the all-encompassing horror to a more pointed one.” Fady Joudah writes to me in Arabic: “It’s unbearable that we all know a silence will soon descend on Gaza when hunger takes hold of them—the voices whose words we follow and wait for every hour.”

I panic.

I think of friends in Gaza—but also of many others I don’t know but follow obsessively on social media, checking their pages every few hours as if feeling for the pulse of an ailing loved one. I think of Anas al-Sharif, whose body has grown thinner and frailer before our eyes as he documents two years of genocide. I think of Nima Hasan, whom I only began following a few months ago, awed by her ability to speak from the darkest depths with clarity, force, and, at times, a biting humor that pins me in place. Everything else outside Nima’s voice shrinks into nothing but a guilty distraction from Gaza.

The next day, Joudah writes again. He shares a poem Nima had sent him that morning—a poem she had just written. “I love you is enough,” she says. The complete sentence, housed in a single Arabic word, أحبّك, suffices when the world closes in and there is no room for longer declarations, for the leisure of language and its constructions. “I love you” is enough to resist with, to fight with, to live with for a moment—and perhaps to survive. I read it once, then twice.

أحبّك

العبارات الطويلة تحتاج جدراناً ومخيماً

وصبية لها جديلة من قمح

تحمل ملعقة سكر بين أناملها

مثل غيمة ملونة

أو موسماً ينمو فيه قصب السكر.

It feels like an impossible poem for Nima to have written in this moment. But then again, a real poem is never only of the moment. A real poem defeats time, every time. And here, Nima writes a poem that time will have to accommodate, will have to make room for—whether there are walls to write on or not.

On August 1st, a young man arrived at Odeh Hospital in Gaza—a martyr. In his pocket, the medical staff found a crumpled napkin with the words “I love you so much” written in English. He must have held onto it for a long time.

Her name was likely Hiba. She signed the message: “from the one who loves you, Habboush.” She had written it first in black ink, then traced it in red. They must have had time—perhaps sitting in a café by the sea, unhurried. There was time. She took her time. In the corner, she drew a heart, colored it in, pierced it with an arrow. She gave the arrow a head and a tail, and at either end she wrote two initials: A and H. A small, ordinary miracle—this love. She had no idea that death, with its blunt hand, would reveal her small secret and turn it into myth. “I love you so much,” she confessed, playfully. She didn’t know he would carry her love all the way to the end—grasping it in his pocket at the edge of time.

Gaza lives and traces for the rest of us paths to survival. When the world collapses and language fails, as it does every minute now, Gaza reminds us that between two lovers, between a mother and her child, a girl and the house she longs for, a boy and the orange grove where he once ran, a man and his beloved, a people and their homeland—against time and its monsters—I love you is enough.

Nima Hasan is a Palestinian poet surviving genocide in Gaza, insisting on poetry that overcomes the most horrific timelines. She is a living Palestinian poet in every sense. Her voice and her language shame and expose the politics of necromancy that pass as solidarity, a necromancy that requires a compromised Palestinian voice or a broken Palestinian body to hold up. Nima’s poetry uncompromisingly resists and exposes that hypocrisy. It is an example of “Palestine in Arabic” that Joudah tells us will liberate itself and us in its course. Her writings lay bare our failures and the many small deaths we die each day before the enormity of life, or what remains of it, in Gaza.

—Huda Fakhreddine, translator

“I love you—

Force the city to hear it out loud.”

—Nima Hasan (trans. Huda Fakhreddine)

Old Song

by Nima Hasan

(translated from the Arabic by Huda Fakhreddine)

“I love you” is enough.

A longer phrase requires sprawling walls, refugee camps,

and a girl with braids long as wheat fields,

a candy swirl the color of a rainbow cloud

between her fingers.

A longer phrase requires a season

when sugarcane grows.

“I love you” is enough,

so write it then,

on a large piece of cloth,

to sustain the mosque-goers,

those servants of the Merciful,

and the peddlers of sweetened drinks.

“I love you” will become a litany

for the ruined street.

All will recite it:

the loose tobacco seller,

the flour thief,

and those who own

a loaf of bread,

an empty bullet,

and a donkey with a broken cart.

I will also provide you with another list—

the names of those who were killed,

those who left the city without “I love you,”

those who breathed through stuffed holes,

longed for a trace of perfume

in a smuggled bottle.

See there, the checkpoints are opening their arms.

I love you—

say it again

like a rebel

or a soldier

who misread the map.

Mothers are searching for henna,

for the Zawiya market,

for the t̩asht of dough in the darkness of tents.

I love you—

say it again.

Give an old song

a chance to explain itself.

A white strand of hair

will light your path.

A lantern,

a sprig of basil,

and a country

that walks alone

without losing its way

will then be yours.

I love you—

Force the city to hear it out loud.

Doesn’t the tribal code grant men a minaret?

Then raise your voice to the greater one,

before sin falls and the last leaf drops.

Shadows betray their trees,

their heads bare,

their necks a guide for the hungry.

This fear—burn it.

And squeeze the mothers’ breasts,

mix their milk with the fig’s.

Let the child grow wild and strong.

Let him collect his baby teeth

behind pursed lips

and swallow the tumbling words,

before he speaks them

in a fit of tears.

I love you—

until the child cries himself to sleep.

Throw your instincts wide open.

Summon the notary

before he swears the oath,

and leave all your inheritance

to a man who waged a war

he had nothing to do with,

a man who called out across the land:

“I love you,”

and then set all the gardens ablaze

أغنية قديمة

العبارات الطويلة تحتاج جدراناً ومخيماً

وصبية لها جديلة من قمح

تحمل ملعقة سكر بين أناملها

مثل غيمة ملونة

أو موسماً ينمو فيه قصب السكر.

ستكتبها إذن

على قطعة قماش كبيرة

ليكتفي بها رواد المساجد

وعباد الرحمن

وبائع الشراب المحلى.

ستصبح أذكاراً

للشارع المهدوم،

لبائع الدخان العربي

وسارق الطحين.

سيتلوها من يملك

رغيف خبز

ورصاصة فارغة

وحماراً بعربة مكسورة.

سأبلغك بقائمة من قتلوا

وتركوا المدينة دونها

من تنفسوا من ثقوب مطوية

واشتهوا رشة عطر

داخل زجاجة مهربة.

المعابر تفتح ذراعيها،

أحبك.

أعد قولها

كثائر أغنية قديمة

أو جندي أخطأ قراءة الخريطة.

الأمهات يبحثن عن الحناء

وعن سوق الزاوية

وعن (طشت) العجين في عتمة الخيام.

أحبك

أعد قولها

امنح أغنية قديمة فرصة شرح نفسها.

الشعرة البيضاء

ستضيئ لك الطريق.

سيصبح لديك مصباح

وعود من ريحان

وبلاد تمشي وحدها

دون أن تتوه.

أحبك

أجبر المدينة على سماعها جهراً.

عرف القبيلة جعل للرجال مئذنة.

كَبّر قبل أن يسقطَ الذنب،

قبل أن تسقط الورقة الأخيرة.

الأشجار يخونها الظل،

رؤوسها مكشوفة

وأعناقها دليل للجوعى.

أحرق هذا

الخوف.

اعصر أثداء الأمهات

وامزجه بحليب التين

دع الطفل يكبر بمزاج عال

يجمع أسنانه اللبنية

بزمة شفاه

يبتلع تعثر الكلمات

ينطقها

بوصلة بكاء حارة.

أحبك

حتى يدركه النوم.

افتح غرائزك على مصراعيها.

استدعٍِ ِ كاتب العدل

قبل أن يحلف يمين الولاء.

وسجلْ أرثك كله

لرجل

صنع حرباً

لا ناقة له فيها

ولا جمل،

ونادى في البلاد

أحبك

ثم أحرق الحديقة.

This poem was first published in English with LitHub, and is republished with the original Arabic here with their permission.

Nima Hasan, a mother and single caretaker of seven children, is a writer, poet, and social worker from Rafah. Her published works in Arabic include the novels Where the Flames Danced and It Was Not a Death and the book Letters from a Perpetrator. Her poetry has been published and translated widely in print and online publications. She was awarded the Samira al-Khalil Prize in 2024 and a selection of her writings during the genocide were published bilingually, in Arabic and French translation by Souad Labbize, titled Be Gaza (Les Lisières, January 2025).

Huda Fakhreddine is a writer, translator, and Associate Professor of Arabic Literature at the University of Pennsylvania. She is the author of Metapoesis in the Arabic Tradition (Brill) and The Arabic Prose Poem: Poetic Theory and Practice (Edinburgh University Press), and the co-editor of The Routledge Handbook of Arabic Poetry (Routledge). Her translations include Jawdat Fakhreddine’s poetry collection Lighthouse for the Drowning (BOA Editions), The Universe, All at Once: Selections from Salim Barakat (Seagull Books), and Palestinian: Four Poems by Ibrahim Nasrallah (World Poetry). She is also the author of a book of creative nonfiction, Zaman saghīr taḥt shams thāniya (A Brief Time Under a Different Sun) and a poetry collection, Wa min thamma al-ālam (And Then the World). She is co-editor of Middle Eastern Literatures.